Episode 1

Friday April 18th, 2014.

Mokpo, South Korea.

He’d seen the ferry sink on TV, one slice at a time, until all that was left was the protruding section of the stem bulb that reminded him of a beached blue whale. He took a shower, packed his things, and left his apartment.

Two days later Hang-Kwong’s hair looked like a handful of black weeds sprouting from the sea.

He pulled out the regulator’s mouthpiece and gasped. He breathed deeply, exhaled and breathed again. The smell of salt and smoke and oil. The taste of blood on his tongue. He didn’t know where it came from.

There’s a couple, he shouted to the tender waiting for him at the starboard of the bright orange zodiac. A boy and a girl. They’re still hugging. I’ll need to go again.

The tender nodded and offered him his hand.

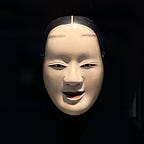

He’d seen horror again, but the mask concealed his tears.

It was his third dive of the day, the third time in less than six hours that he’d gone in looking for bodies. He’d found many. The first attempts to pull them out the past two days had failed. The first line snapped. A diver almost died. A storm raged against the coast. Since the second search line had been set, though, they had spotted many and extracted thirteen. Hang-Kwong had spotted six of them and pulled out a boy and a girl himself.

The cold stung his face and the endless currents swayed his body like a rag doll. Although the many search lights shone like little suns above, down there the visibility was of about 20 centimeters. A maze of narrow passages blocked by furniture or bodies. Cans, clothes, shoes, sandals, cell phones. Some dolls. The personal possessions of the young. Floating debris everywhere, like the aftermath of a piñata.

Who are those? He asked the tender once on board.

Americans, said the tender looking at the large wasp-class ship, a large white ‘6’ painted on the gray walls of its accommodation. They just arrived. You can rest, he said, they brought more divers.

For a moment, although several Helicopters hovered above their heads and dozens of boats loaded and unloaded hundreds of men, Hang-Kwong heard nothing besides his own heart beating.

I’m going in.

You know, said the tender, you don’t even have to be here. Those guys are pros, and now there are hundreds of them.

Where were they two days ago when the kids were drowning?

The tender handed him a cup of hot tea.

One of the mothers found the vice-president of the school hanging from a tree outside the gymnasium.

In Seoul?

Jindo. He was one of the first and few they rescued. He used his own belt.

What about the captain?

The police issued arrest warrants. He will be caught soon.

Good.

Hang-Kwong handed back the cup to the tender and asked him to help him get ready.

He left the water after the fourth dive. His heart beat hard against his chest, his balance was affected, and inside his head felt as if a large and strong hand had wrapped around his brain and was squeezing the juice out of it.

He found a girl this time. Age fourteen or fifteen. She was alone, her face and body crushed against one of the ferry’s windows, many of her fingers broken. She had been hitting that window for God knows how long.

He looked back at the sea for the last time that day. Orange flares like shooting stars lit the sky and he saw the hundreds of islands beyond the rescue vessels. He thought they looked like bodies floating face down.

After stopping by the portable toilets, he washed himself and changed his clothes at one of the tents set around the port. He picked one out of a row of empty cots. He said hi, but the few men already in were trying to sleep or were too tired to engage in conversation. He ate in silence from a bag of salty snacks and had beer and then a glass of Soju. And then another. He drained the little green bottle in less than thirty minutes.

Before he fell asleep he heard a whisper in his ear. Waves brought by the wind, he thought. He stared at the ceiling of the tent and recalled how he had pulled the first kid from the hull. He found him near an entrance. He turned the body around to avoid seeing the boy’s face, grabbed him under his armpits, and swam backwards following the line. The girl had locked herself in one of the toilets, perhaps hoping for the door to keep the water out. Unlike the boy’s, her eyes were open.

That night Hang-Kwong slept little less than three hours. He saw a dream, and in the dream he saw a tiny bird, grass-green body and white eyes, fall into a pool and about to drown. He jumped in and scooped the bird out of the water. He placed the fragile bird with care on the axil of a nearby tree. The orphaned creature looked at him. It seemed both skeptical and grateful. A large and old bird, some sort of thick-billed parrot missing patches of feathers here and there, suddenly came down from an upper branch, opened its beak wide, and swallowed the tiny bird whole.